From approximating math functions to computer vision

Now that we’ve covered how gradient descent works and how we can estimate any function by combining linear and non-linear functions we are equipped to resolve some more interesting problems. Building on top of the samples in the first post of this series we will look at the problem of identifying what number appears in an image:

picture +--------+ identify number

----------------->| f(x) |---------------->

+--------+

Digit classifier with linear functions

Let’s start with a simple example such as a fitting a function that tells us if a number is a 5 or not based on the MNIST dataset (a database of handwritten numbers in image format).

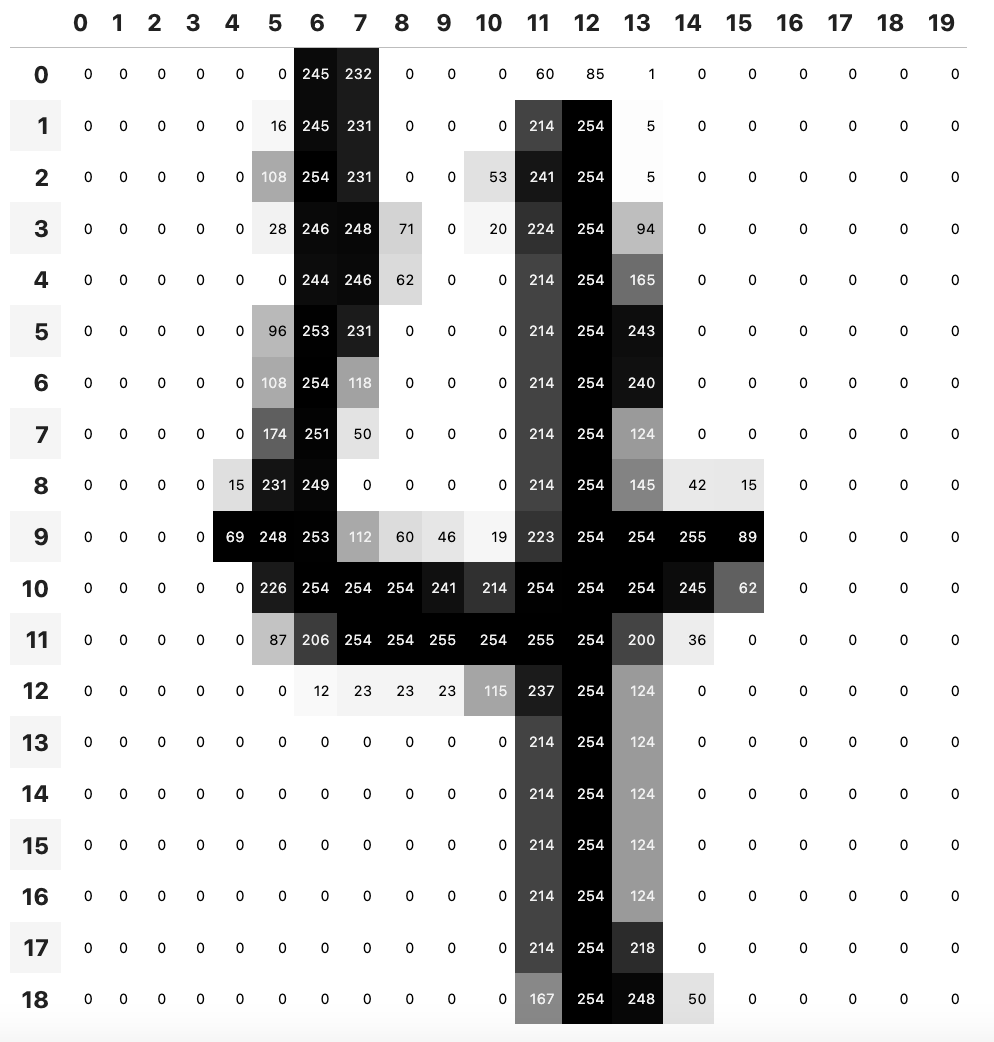

The first question that comes to mind is how do we represent a 28x28 pixels image so that our linear functions can understand it. We can rely on Python PIL and PyTorch which allow us to convert an input image to its tensor representation. Since the MNIST database stores images in grayscale (L mode) each pixel will be a number ranging from 0 to 255.

We can build on top of our last article sample and consider each pixel of a 28x28 (784 pixels) image to be a separate input:

+---------+ x weight1 + bias +--------+

| pixel 1 |-------------------------+---------->| output |

+---------+ | +--------+

|

+---------+ ... |

| ... |-------------------------+

+---------+ |

|

+-----------+ x weight784 |

| pixel 784 |-----------------------+

+-----------+

Data preparation

First we need to load our x and y values. In the prior article we just made up some x values in a range and got the ys by applying some quadratic function. This time we need some images as x and wether they are a 5 or not as y. We can set our targets (y values) to be either a 1 if the picture is a 5 or 0 if it isn’t so our Neural Network would be trying to approximate to either 0 or 1 given an image, e.g.:

targets = [0, 1, 1] # a picture that is not a five followed by two that are 5s

predictions = [0.3, 0.9, 0.8] # a made-up prediction given by a neural network

We can rely on fast.ai to load our images, a sample for the 5s would look like the following but we could load any number from MNIST the same way:

path = untar_data(URLs.MNIST)

fives_filenames = (path/'training'/'5').ls().sorted()

fives_tensors = [tensor(Image.open(o)) for o in fives_filenames]

fives = torch.stack(fives_tensors).float()/255

Note that as a best practice we are normalising the pixel values to numbers between 0 and 1 instead of having to handle numbers from 0 to 255. It stabilizes the training by keeping inputs within a smaller range and far from the extremes of activation functions while also allowing to load images from distinct formats

We can now load all the images we want to be able to recognise, let’s start only with 5s and 4s for the sake of simplicity:

x = torch.cat([fives, fours]).view(-1, 28*28)

y = tensor([1]*len(fives) + [0]*len(fours)).unsqueeze(1)

We are using the view and unsqueeze functions to ensure our tensors have the right dimensions:

- for

xwe make sure each image is a single dimension so we can input it in our linear functions and - for

ywe make sure each output is in its own row so that we can use broadcasting in our loss and accuracy functions later on

x.shape, y.shape

# (torch.Size([11263, 784]), torch.Size([11263, 1]))

Loss function

Now we need a loss function for our gradient descent implementation. In our prior article we used F.l1_loss function to calculate the Absolute Mean Error between all predictions and the actual outputs of the data we were approximating. Now we aren’t comparing two real values distance but how far from a 5 are we, so we need a loss function that can handle binary classification instead of continuous regression.

One possible loss function would be to have a function that counts the number of 1s in the actual data (targets) and compare it to our predicitons (did we estimate the same 5s?):

# broadcasting PyTorch tensors to count correct predictions

corrects = (predictions>0.0).float() == targets

# convert booleans to 0/1 and take the mean to know how many 1s we got

corrects.float().mean()

That would make a great metric to know the accuracy of our system - but not a great loss function. Tiny changes in the weights will only change the final result when a prediction flips from 0 to 1 or viceversa so the gradient would be constant most of the time and gradient descent would struggle to optimise the weights.

An alternative approach would be to quantify how far we are from the 1s and 0s instead of just counting, hence optimising for either 0 or 1 classifications:

torch.where(targets==1, 1-predictions, predictions).mean()

By relying on the torch where function we can calculate a loss function that is more sensible to changes in the weights than just counting the number of 1s because a tiny changes would be accounted for. E.g. if some particular image prediction should be marked as a 5 the prediction value should be 1. If our Neural Network predicts 0.6 instead of 0.5 it got a bit closer to the real value (that wouldn’t happen with the accuracy function described in the first attempt).

One major problem of the loss function above is that it assumes that our Neural Network is predicting values between 0 and 1 which won’t be the case since we aren’t applying any non-linear function at the end of the NN. A simple solution to the problem would be to apply predictions.sigmoid() to the tensor before the loss function:

def mnist_loss(predictions, targets):

predictions = predictions.sigmoid()

return torch.where(targets==1, 1-predictions, predictions).mean()

Gradient Descent

With that we are ready to implement basic gradient descent as we did in the last article. The only difference is that we are using 784 (28x28) input parameters instead of 1 and adjusted the names to be closer to neural networks jargon:

def linear1(x): return x@weights + bias

def calc_grad(x, y, model):

preds = model(x)

loss = mnist_loss(preds, y)

loss.backward()

def train_epoch(model, lr, params):

calc_grad(x, y, model)

for p in params:

p.data -= p.grad*lr

p.grad.zero_()

def init_params(size, std=1.0): return (torch.randn(size)*std).requires_grad_()

With that we are ready to run some epochs (in this case we are running through all data each epoch so each epoch has only 1 gradient descent step):

weights = init_params((28*28,1))

bias = init_params(1)

lr = 1.

params = weights,bias

for i in range(100):

train_epoch(linear1, lr, params)

Which results in the following loss reduction curve:

That doesn’t really tell us how will our model perform but tells us how well Gradient Descent is doing with the loss function we have defined on top of our training data. To have a better understanding of how our model behaves and generalises we need to check with data it has never seen before (validation set) and look at its accuracy metrics (not loss).

We can leverage the validation set given in the MNIST dataset and execute the accuracy calculation lines we looked at above:

# exactly same data loading lines as for our training set

validation_fives_filenames = (path/'testing'/'5').ls().sorted()

validation_fives_tensors = [tensor(Image.open(o)) for o in validation_fives_filenames]

validation_fives = torch.stack(validation_fives_tensors).float()/255

validation_fours_filenames = (path/'testing'/'4').ls().sorted()

validation_fours_tensors = [tensor(Image.open(o)) for o in validation_fours_filenames]

validation_fours = torch.stack(validation_fours_tensors).float()/255

validation_x = torch.cat([validation_fives, validation_fours]).view(-1, 28*28)

validation_y = tensor([1]*len(validation_fives) + [0]*len(validation_fours)).unsqueeze(1)

# accuracy calculation

predictions = linear1(validation_x)

corrects = (predictions>0.0).float() == validation_y

corrects.float().mean()

Which results in an accuracy of 93.01%.

Adding a non-linear function

A natural next step as explained in the last article is to introduce non-linearity between our input and our output for further prediction flexibility:

+---------+ x weight1 + bias1 +------+ x weight + bias +--------+

| pixel 1 |-------------------------+---->| Sigm |---------+------->| output |

+---------+ | +------+ | +--------+

| |

+---------+ ... | +------+ |

| ... |-------------------------+---->| Sigm |---------+

+---------+ | +------+ |

| |

+-----------+ x weight784 + bias784 | +------+ |

| pixel 784 |-----------------------+---->| Sigm |---------+

+-----------+ +------+

What that would imply for our code is that we would need to replace our linear1 function with:

def simple_neural_net(x):

res = x@w1 + b1

res = res.sigmoid()

res = res@w2 + b2

return res

and our gradient descent code becomes:

w1 = init_params((28*28,28*28))

b1 = init_params(28*28)

w2 = init_params((28*28,1))

b2 = init_params(1)

lr = 1.

params = w1, b1, w2, b2

for i in range(100):

train_epoch(simple_neural_net, lr, params)

Notice that w1 is a matrix of 784x784 rows per columns instead of 784x1 as we did above. That’s because we have added a Sigmoid for each single pixel in our sample. We could have added any other number of Sigmoids in our hidden layer. If that’s confusing it might be worth to check out this video.

After running the code with non-linearity we get the following loss curve which has a better performance:

The only line we switched is:

-predictions = linear1(validation_x)

+predictions = simple_neural_net(validation_x)

Running the accuracy for this sample we go up to 95.3% which is already pretty good knowing how little we’ve been training this very simple neural network.

The fact that we added the same number of nodes as input parameters is random. Usually they won’t match since the inputs might be way too many. Since we are looking at a fully connected neural network each node connects to all inputs so it would represent a learnt feature of a particular combination of pixels 784 pixels. If we reduce the nodes to 50 instead, we get an accuracy of 94%.

w1 = init_params((28*28,50))

b1 = init_params(50)

w2 = init_params((50,1))

b2 = init_params(1)

In next posts we will explore Stochastic Gradient Descent and how we can leverage more Pytorch and Fast.ai libraries to simplify our code. For more information look at chapter 4 of the fast.ai book or its associated Jupyter notebooks.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: