Gradient Descent from scratch

The following article describes how Gradient Descent works which lies at the core of Neural Networks. Don’t worry like I did, only basic Algebra and Calculus are needed to understand well the underlying math and I’ll go through it in detail.

Problem statement

Let’s start defining what are we trying to achieve. Given an input, we want to find a function f(x) that would predict an output with enough accuracy for it to be useful for us as humans.

input +--------+ output

------>| f(x) |------->

x +--------+ y

Let’s look at some samples of some functions we might be interested in:

time +--------+ height of ball

----------------->| f(x) |---------------->

+--------+

picture +--------+ identify number

----------------->| f(x) |---------------->

+--------+

audio song +--------+ genre

----------------->| f(x) |---------------->

+--------+

text +--------+ topic

----------------->| f(x) |---------------->

+--------+

The outputs depend on the inputs and we can find a mathematical function that relates the two. Finding what that function is would allow us to get an output prediction for each input as long as the function resembles the real world closely enough!

And since math functions do represent real world phenomenons, let’s just use one such example. The following quadratic function tells us the height of a thrown ball upwards for a particular time t:

where:

-

gis gravity on earth level -

v0is the initial throwing speed -

h0is the initial height of the throw

If we wanted to predict the height at a particular time (e.g. after 2 seconds) we just need to know the initial throwing speed v0 and height h0 and we can easily resolve h(2) and get our answer.

What if we don’t know the actual formula nor initial throwing/height speed but only have observations from nature? Let’s say a ball was thrown vertically and we installed a sensor which gave us 15 measurements of all the heights the ball went through during 5 seconds:

{

"type": "scatter",

"data": {

"labels": [0.0, 0.35714285714285715, 0.7142857142857143, 1.0714285714285714, 1.4285714285714286, 1.7857142857142858, 2.142857142857143, 2.5, 2.857142857142857, 3.2142857142857144, 3.5714285714285716, 3.928571428571429, 4.285714285714286, 4.642857142857143, 5.0],

"datasets": [

{

"label": "Height of thrown ball",

"fill": false,

"lineTension": 0.1,

"backgroundColor": "rgba(75,192,192,0.4)",

"borderColor": "rgba(75,192,192,1)",

"borderCapStyle": "butt",

"borderDash": [],

"borderDashOffset": 0,

"borderJoinStyle": "miter",

"pointBorderColor": "rgba(75,192,192,1)",

"pointBackgroundColor": "#fff",

"pointBorderWidth": 5,

"pointHoverRadius": 10,

"pointHoverBackgroundColor": "rgba(75,192,192,1)",

"pointHoverBorderColor": "rgba(220,220,220,1)",

"pointHoverBorderWidth": 2,

"pointRadius": 1,

"pointHitRadius": 10,

"data": [29.128620665942556, 35.24960579584343, 42.16851569710115, 44.90160627870316, 46.63155173360897, 52.22662725576406, 52.86940417603709, 50.56015123210324, 46.128434083285384, 44.53718441643712, 40.57409445955629, 32.19438620635332, 24.50774696452207, 17.09045405656899, 7.26565053601106],

"spanGaps": false

}

]

},

"options": {

"scales": {

"x": {

"display": true,

"title": {

"display": true,

"text": "x = time in seconds"

}

},

"y": {

"display": true,

"title": {

"display": true,

"text": "y = height in meters"

}

}

}

}

}

In this example we want to be able to predict where the ball will be at a certain point in time without knowing the h(t) formula. For now let’s assume the phenomenon follows some quadratic function:

So we are looking for coefficients a, b and c that will produce values as similar as possible to the input data we have provided through our sensors.

For example, if a = 3, b = 2, c = 1 we would have \(f(x)=3x^2 + 2x + 1\). Take one of our real inputs (e.g. x = 0.714), and we see that \(f(0.714) = 3.957388\). From our input data we know that y = 42.169 for that value of x so the difference (or error) of our prediction is \(y - f(x)\) which is 42.169 - 3.957388 = 38.211612. We are still far from having a function that predicts well our ball trajectory!

Our goal is to minimise the error between our input data and a quadratic function we are looking for (by choosing a, b and c coefficients).

How can we measure the error of the whole function and not for a single point only?

Calculating errors

For a single point we relied on their distance \(y - f(x)\). We want to know the error across all input data we have so we can properly evaluate if our function is good enough. We can achieve that by just taking the mean of all individual errors! For convenience, instead of using function notation we can use our dependant variable name (like we do with y), i.e. \(\hat y = f(x)\). Our mean would look like this:

where n goes from the first sensor datapoint to the last (0 to 15 in our example). The issue with this function is that our predictions might also be negative (if \(\hat y_i > y_i\)) which would screw the mean. We need a more resilient function and a common way to bypass that problem is to use the square of a number since a squared negative result would become positive:

That is the Mean Square Error (MSE) function. It has a problem though, squaring each number implies that our error will be way higher than the actual y values of our function. In our example, our error was 38.211612 which when squared already goes up to 1460.12729164. If we aren’t willing to handle such big numbers in our errors we can take the square root on top of our error which would reduce our number again:

That is the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) function.

One of the main issues of both functions is the squaring process which has sensitivity to outliers (bigger numbers will be way bigger, numbers close to 0 will be way smaller). To avoid the issue, we could get the absolute value of the difference instead:

\[MAE = \frac 1 n \sum _{i=1} ^n |y_i - \hat y_i|\]That is the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) function and we will be using it to calculate how far are we with our predictions from the sensor values. One of its major drawbacks is that it’s not differentiable and we’ll explain shortly why is that important.

Now that both our problem statement and measure of success are clear we need a resolution method!

Solution

In the sample above we chose random values for a = 3, b = 2 and c = 1 which results in an error of MAE=32.98. The lower the error, the better we are predicting our input data. How can we adjust a, b and c iteratively while minimising the error?

One rather tedious approach would be to adjust the coeficients randomly and watch how MAE changes with each coefficient adjustment (for the better or the worst) until we achieve to reduce the MAE enough. Luckily there is a much better approach through differentiation.

Differentiation

The question that has just arised is how much would a function change by a change on one of its parameters. In particular, we are asking how much would MAE output change by a slight change on one of its parameters (e.g. a).

Let’s start with a simpler example, a line \(f(x) = x\):

{

"type": "line",

"data": {

"labels": [0,1, 2],

"datasets": [

{

"label": "x",

"fill": false,

"lineTension": 0.1,

"backgroundColor": "rgba(75,192,192,0.4)",

"borderColor": "rgba(75,192,192,1)",

"borderCapStyle": "butt",

"borderDash": [],

"borderDashOffset": 0,

"borderJoinStyle": "miter",

"pointBorderColor": "rgba(75,192,192,1)",

"pointBackgroundColor": "#fff",

"pointBorderWidth": 5,

"pointHoverRadius": 10,

"pointHoverBackgroundColor": "rgba(75,192,192,1)",

"pointHoverBorderColor": "rgba(220,220,220,1)",

"pointHoverBorderWidth": 2,

"pointRadius": 1,

"pointHitRadius": 10,

"data": [0, 1, 2],

"spanGaps": false

}

]

},

"options": {

"scales": {

"x": {

"display": true,

"title": {

"display": true,

"text": "x"

}

},

"y": {

"display": true,

"title": {

"display": true,

"text": "y"

}

}

}

}

}

By looking at the plot it’s easy to conclude that for each unit increment of x, y would increment by 1. This is also known as the slope of the tangent line at that point (or rate of change) and it’s described by \(slope = \frac {rise} {run}\), i.e. \(slope = \frac {y_2 - y_1} {x_2 - x_1}\).

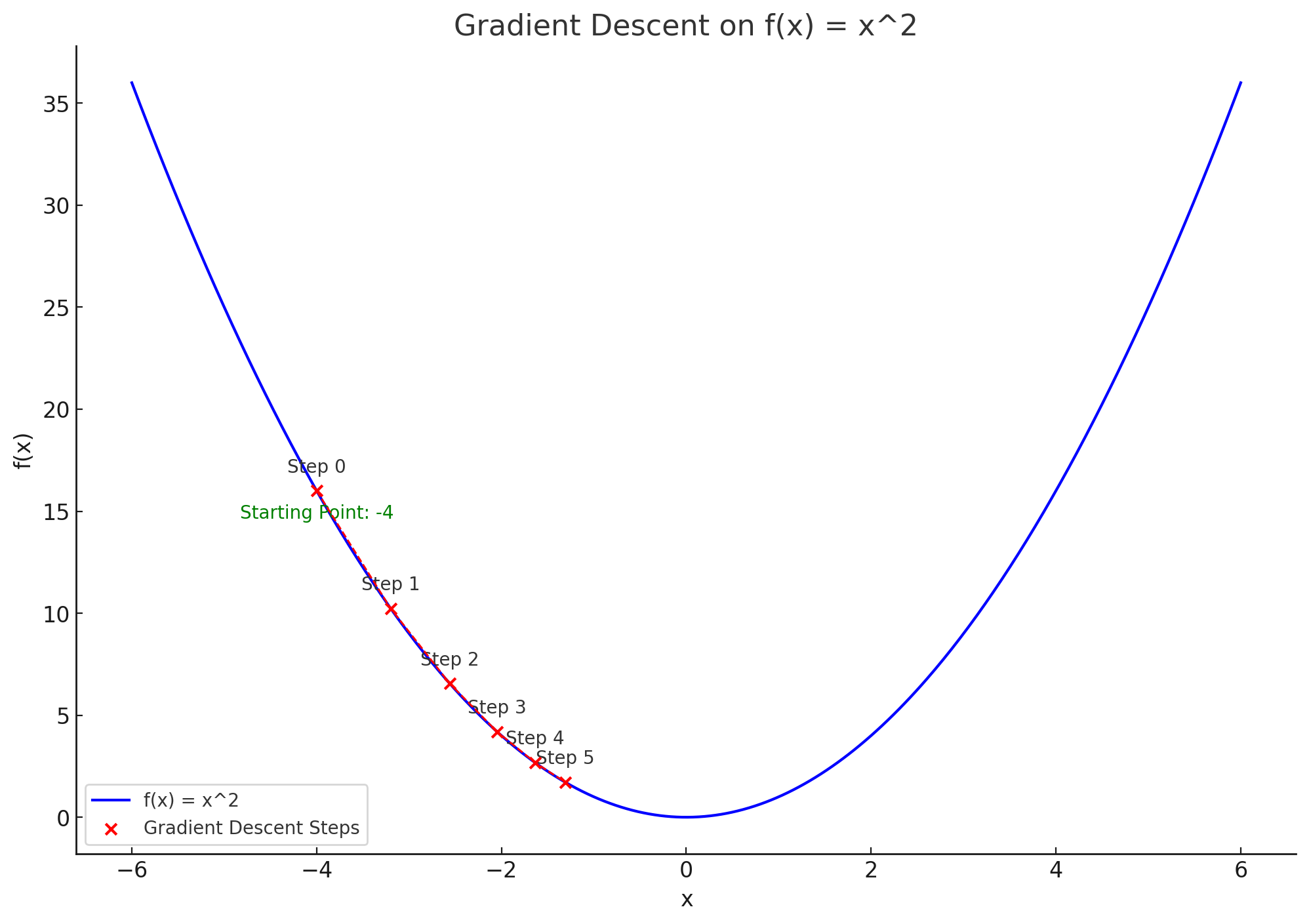

Let’s now have a look at a more complicated example, a non-linear function like \(f(x) = x^2\):

{

"type": "line",

"data": {

"labels": [-4, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4],

"datasets": [

{

"label": "x^2",

"fill": false,

"lineTension": 0.3,

"backgroundColor": "rgba(75,192,192,0.4)",

"borderColor": "rgba(75,192,192,1)",

"borderCapStyle": "butt",

"borderDash": [],

"borderDashOffset": 0,

"borderJoinStyle": "bevel",

"pointBorderColor": "rgba(75,192,192,1)",

"pointBackgroundColor": "#fff",

"pointBorderWidth": 0,

"pointRadius": 0,

"pointHitRadius": 10,

"data": [16, 9, 4, 1, 0, 1, 4, 9, 16],

"spanGaps": false

}

]

},

"options": {

"scales": {

"x": {

"display": true,

"title": {

"display": true,

"text": "x"

}

},

"y": {

"display": true,

"title": {

"display": true,

"text": "y"

}

}

}

}

}

Here it becomes slightly trickier to know by how much would y change if x changed by one because depending on where you look you would get a different slope due to the lack of linearity in our function. For example from x=4 to x=3 it’s \(\frac {16 - 9} {4 - 3} = 7\) but from x=3 to x=2 we get \(\frac {9 - 4} {3 - 2} = 5\).

Here is where differentiation kicks in! If we zoom in the slope for x further then 3 to 2 and look at values closer to 2 we would be getting closer to the real slope of the tangent line in that point (x=2):

-

3.000to2: \(\frac {9 - 4} {3 - 2} = 5\) -

2.500to2: \(\frac {6.25 - 4} {2.5 - 2} = 4.5\) -

2.250to2: \(\frac {5.0625 - 4} {2.25 - 2} = 4.25\) -

2.010to2: \(\frac {4.0401 - 4} {2.01 - 2} = 4.01\) -

2.001to2: \(\frac {4.004001 - 4} {2.001 - 2} = 4.001\)

Looks like we are approaching the slope of 4! We could try the same process from 1 to 2 and we would be approaching the same number. Since y = f(x) we could express the difference (or slope of tangent line) of any the two points like this:

As we have seen above we can pick any \(x_2\) that is close enough to \(x_1\) to get our slope so we can formalise that with any constant \(x_2 = x_1 + h\) hence getting:

\[\frac {f(x_1 + h) - f(x_1)} {x_1 + h - x_1} = \frac {f(x + h) - f(x)} { h }\]If we want to get a point very close to x + h we can look at the limit of h towards 0:

That approximation to a point is what differentiation is all about! Let’s try to resolve that limit for \(x^2\):

\(\lim _{h\to 0} \frac {f(x + h) - f(x)} { h } =\) \(\lim _{h\to 0} \frac {(x + h)^2 - x^2} { h } =\) \(\lim _{h\to 0} \frac {x^2 + h^2 + 2xh - x^2} { h } =\) \(\lim _{h\to 0} \frac {h^2 + 2xh} { h } =\) \(\lim _{h\to 0} \frac {h(h+2x)} { h } =\) \(\lim _{h\to 0} h+2x = 2x\)

We just derived \(x^2\)! If you recall the power rule it tells us that given \(f(x) = x^n\) it’s derivative is:

- Prime notation: \(f'(x) = nx^{n-1}\)

- Leibniz notation: \(\frac d {dx} f(x) = nx^{n-1}\)

- Euler notation: \(\frac \partial {\partial x} f(x) = nx^{n-1}\)

There are more rules for differentiation which will allow us to get the slope (or rate of change) for any differentiable function (continuous, smooth and without tangents).

Actually the slope we got earlier by approximating x=2 was 4, i.e. \(slope = f'(x^2) = 2x = 2*2 = 4\).

Impact of changing each parameter

At this point, we have defined our problem statement, we are able to measure its’ error for certain parameters and we are able to see how much a change in each parameter impacts that error by using the derivatives of each parameter (or gradient)! As a reminder, the function we are trying to minimise as described above is the MAE:

We will start by looking at what’s the impact of each change in a to that function (so that we can find an a that minimises its value) by differentiation. Our function is composite, since MAE depends on the output of our quadratic function. We need to apply the Chain Rule to be able to take the derivative, which states:

Applied to our case, the inner function g(x) is:

and the outer function f(x) is:

Resolving the derivative of our MAE to find out the impact of a through the chain rule, we get:

\(\frac \partial {\partial a} MAE = \frac \partial {\partial a} \frac 1 n \sum _{i=1} ^n |y_i - \hat y_i| =\) \(\frac \partial {\partial {\hat y_i}} \frac 1 n \sum _{i=1} ^n |y_i - \hat y_i| * { \frac \partial {\partial a} \hat y_i } =\) \(\frac 1 n \sum _{i=1} ^n \frac \partial {\partial {\hat y_i}} |y_i - \hat y_i| * { \frac \partial {\partial a} \hat y_i }\)

Now we have two derivatives to resolve, let’s do that one by one:

- \[{ \frac \partial {\partial {\hat y_i}} |y_i - \hat y_i| }\]

- \[{ \frac \partial {\partial a} \hat y_i }\]

Earlier we mentioned that one problem with MAE is that it’s not differentiable, and that’s because of the shape of the absolute function |x|:

{

"type": "line",

"data": {

"labels": [-1,0, 1],

"datasets": [

{

"label": "x",

"fill": false,

"lineTension": 0.1,

"backgroundColor": "rgba(75,192,192,0.4)",

"borderColor": "rgba(75,192,192,1)",

"borderCapStyle": "butt",

"borderDash": [],

"borderDashOffset": 0,

"borderJoinStyle": "miter",

"pointBorderColor": "rgba(75,192,192,1)",

"pointBackgroundColor": "#fff",

"pointBorderWidth": 5,

"pointHoverRadius": 10,

"pointHoverBackgroundColor": "rgba(75,192,192,1)",

"pointHoverBorderColor": "rgba(220,220,220,1)",

"pointHoverBorderWidth": 2,

"pointRadius": 1,

"pointHitRadius": 10,

"data": [1, 0, 1],

"spanGaps": false

}

]

},

"options": {

"scales": {

"x": {

"display": true,

"title": {

"display": true,

"text": "x"

}

},

"y": {

"display": true,

"title": {

"display": true,

"text": "y"

}

}

}

}

}

Whenever x=0 (\(\hat y_i - y_i = 0\)), we don’t know what’s the slope of the line! Looking from the left its negative and looking from the right it’s positive. We need to rely on a subdifferentials for this function. For x=0 it gives us a range of [-1, 1]. By convention we will pick the number y=0 when x=0. The other particularities of the absolute function is that it converts all numbers to positive, i.e. if x>0 y=x and if x<0 y=-x.

Now let’s apply the derivative knowing that:

\({ \frac \partial {\partial {\hat y_i}} |y_i - \hat y_i| } = {\begin{cases} \frac \partial {\partial {\hat y_i}} (-y_i + \hat y_i) & {y_i - \hat y_i} < 0 \\ \frac \partial {\partial {\hat y_i}} (y_i - \hat y_i) & {y_i - \hat y_i} > 0 \\ undefined & {y_i - \hat y_i} = 0 \end{cases}} =\) \({\begin{cases} 1 & {y_i - \hat y_i} < 0 \\ -1 & {y_i - \hat y_i} > 0 \\ undefined & {y_i - \hat y_i} = 0 \end{cases}}\)

The other derivative is just a simple application of the Power Rule:

\(\frac \partial {\partial a} \hat y_i =\) \(\frac \partial {\partial a} ax^2 + bx + c = x^2\)

And we got our Quadratic MAE full derivative with respect to a:

\(\frac \partial {\partial a} MAE =\) \({\begin{cases} x^2 & {y_i - \hat y_i} < 0 \\ -x^2 & {y_i - \hat y_i} > 0 \\ undefined & {y_i - \hat y_i} = 0 \end{cases}}\)

Repeating the exact same process for b the only change is the partial derivative of our quadratic:

\(\frac \partial {\partial b} MAE =\) \({\begin{cases} x & {y_i - \hat y_i} < 0 \\ -x & {y_i - \hat y_i} > 0 \\ undefined & {y_i - \hat y_i} = 0 \end{cases}}\)

and the same for c:

\(\frac \partial {\partial c} MAE =\) \({\begin{cases} 1 & {y_i - \hat y_i} < 0 \\ -1 & {y_i - \hat y_i} > 0 \\ undefined & {y_i - \hat y_i} = 0 \end{cases}}\)

Now we have a way to calculate how much of an impact a unit change on a, b or c has on our error function with our quadratic. That vector is our gradient.

Gradient descent

We are all set to find a solution to our original problem statement through Gradient Descent. There is a nice analogy in Wikipedia to help grasp Gradient Descent: a person is in a mountain and wants to go down. There is plenty of fog so the easiest way down is by looking at the slope and going one step at a time downwards all the way until the slope is 0.

The slope in our case is the direction to minimise our error and gradient descent would look like:

- Start with a random values for

a,bandccoefficients (step 0) - Get the slopes for

a,bandc - Update

a,bandcin the opposite direction of the gradient (since we want to decrease the error) by applying a learning rate to ensure we move in small steps (and not whole units) - Repeat until we reduced the error rate enough or reach a slope of 0

A sample in Ruby

Let’s see how the resolution of our original problem would look like in Ruby. First we need the slopes for a, b and c given \(x_i\), \(y_i\) and \(\hat y_i\):

def calculate_mae_gradient_for_abc(x_i, y_i, predicted_y_i)

n = x_i.length

quadratic_partials.map do |partial_derivative|

gradients = x_i.zip(y_i, predicted_y_i).map do |x, y, predicted_y|

abs_subgradient(y, predicted_y) * partial_derivative.call(x)

end

gradients.sum / n

end

end

def abs_subgradient(y, predicted_y)

return 1 if y - predicted_y < 0

return -1 if y - predicted_y > 0

0

end

def quadratic_partials

quadratic_partial_a = -> x { x**2 }

quadratic_partial_b = -> x { x }

quadratic_partial_c = -> _ { 1 }

[quadratic_partial_a, quadratic_partial_b, quadratic_partial_c]

end

Now that we can calculate the gradients we can go down the slope:

def run_gradient_descent(initial_parameters, x_i, y_i, learning_rate = 0.01, iterations = 100000)

predicted_parameters = initial_parameters

for i in 1..iterations do

print "\rRunning iterations.. (#{i}) with learning rate #{learning_rate}"

predicted_equation = quadratic_from_parameters(*predicted_parameters)

predicted_y_i = x_i.map{ |x| predicted_equation.(x) }

gradients = calculate_mae_gradient_for_abc(x_i, y_i, predicted_y_i)

predicted_parameters = predicted_parameters.zip(gradients).map{ |param, slope| param - slope * learning_rate }

end

predicted_parameters

end

We use a small helper to create generic quadratic functions so that we can evaluate the predictions:

def quadratic_from_parameters(a, b, c)

-> x { a*x**2 + b*x + c }

end

Now we can execute gradient descent on our problem! Let’s first see how we generate some fake sensor data, starting with our independent variable x (measured in seconds) that goes from 0 to 5 in 15 steps:

def generate_x_i(from, to, number_of_steps)

step_size = (to - from) / (number_of_steps - 1).to_f

Array.new(number_of_steps) { |i| from + i * step_size }

end

x_i = generate_x_i(0, 5, 15)

Next we are ready to generate values for y. We use a function that follows the equation of a vertically thrown ball introduced in the beginning of the article \(h(t)=−4.9t^2+v0t+h0\) with an initial speed of v0=20 and a height of h0=30. We also add some noise to fake imperfect sensor data:

quadratic_equation = quadratic_from_parameters(-4.9, 20, 30)

y_i = x_i.map { |x| quadratic_equation.(x) }.map { |y| y + y*rand(-0.05..0.05) }

learning_rate = 0.005

initial_random_abc = [521, 123, -120]

predicted_parameters = run_gradient_descent(initial_random_abc, x_i, y_i, learning_rate)

puts "Parameters prediction: #{predicted_parameters}"

and we get:

Running iterations.. (100000) with learning rate 0.005

Parameters prediction: [-5.09634353758922, 20.90880952378543, 29.844999999961708]

Our algorithm predicted the following equation:

\[f(x) = -5.09x^2 + 20.91x + 29.85\]When compared to the ball-throwing equation we have on the top, we see how close we got:

- Predicted values: \(g = -10.18\), \(v0=20.91\) and \(h0=29.85\)

- Actual values we used to generate our (noisy) data: \(g = 9.8\), \(v0=20\) and \(h0=30\)

You can easily calculate the MAE value if needed with:

def mae(x_i, y_i, predicted_parameters)

predicted_equation = quadratic_from_parameters(*predicted_parameters)

predicted_y_i = x_i.map{ |x| predicted_equation.(x) }

differences = y_i.zip(predicted_y_i).map { |y, predicted_y| (y - predicted_y).abs }

differences.sum / differences.size.to_f

end

puts "MAE: #{mae(x_i, y_i, predicted_parameters)}"

which for our sample run was MAE: 1.025.

Conclusion

We have been able to use Gradient Descent to predict the coefficients of a quadratic function with only dirty sample data! We even almost got right the value of gravity! There is a big assumption we’ve done though: we knew our sensor data (throwing a ball vertically) followed a quadratic function.

In a next post we will see how we can generalise what we learnt here to resolve more complicated problems like those mentioned in the beginning that don’t necessarily follow a quadratic function with the help of Rectified Linear Units.

Check this Jupyter notebook for interactive learning material or its’ associated video to grasp better the concepts explained in this article.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: